When John Milton published *Paradise Lost* in 1667, he didn’t just write an epic — he redefined what an epic could be. Rooted in the traditions of Homer and Virgil yet infused with biblical gravitas and Renaissance humanism, Milton’s magnum opus shattered the classical mold to construct something entirely original. His blank verse poem was not only an ambitious theological undertaking, but a linguistic revolution, showcasing the richness and elasticity of the English language in ways that had never been attempted before.

To fully appreciate Milton’s daring, one must first understand the classical epic tradition he was both honoring and subverting. Works like the *Iliad*, *Odyssey*, and *Aeneid* relied heavily on formal structure — meter, invocation of the muse, heroic catalogues, divine intervention — and Milton adopts many of these. Yet, with *paradise lost*, he takes the genre somewhere wholly new. Instead of a martial hero, his protagonist is a fallen angel; instead of patriotic conquest, his theme is cosmic disobedience and spiritual fall. *Paradise Lost* is, in many ways, the anti-epic that still manages to be the ultimate epic.

To fully appreciate Milton’s daring, one must first understand the classical epic tradition he was both honoring and subverting. Works like the *Iliad*, *Odyssey*, and *Aeneid* relied heavily on formal structure — meter, invocation of the muse, heroic catalogues, divine intervention — and Milton adopts many of these. Yet, with *paradise lost*, he takes the genre somewhere wholly new. Instead of a martial hero, his protagonist is a fallen angel; instead of patriotic conquest, his theme is cosmic disobedience and spiritual fall. *Paradise Lost* is, in many ways, the anti-epic that still manages to be the ultimate epic.

What sets Milton apart is not just content, but his linguistic innovation. His use of blank verse — unrhymed iambic pentameter — was bold at a time when rhyme was considered essential for poetic beauty. This choice gave his language a kind of lofty fluidity, unencumbered by the rhyme schemes that could limit expressive range. The poem’s syntax is famously complex, its sentences winding through multiple clauses and allusions, echoing the Latin that Milton so revered. This gives his lines a sculptural quality: weighty, balanced, and profoundly musical.

Milton’s vocabulary is another key element of his stylistic genius. He seamlessly blends Anglo-Saxon grit with Latinate grandeur, combining native English roots with elevated diction borrowed from classical tongues. Words like “infidel,” “oblivion,” “transgression,” and “celestial” populate the poem, giving it a tonal ambiguity that shifts between intimacy and majesty. He doesn’t just use language — he wields it like a sword, at once elegant and devastating.

The poem is saturated with paradox. Satan, for example, is given some of the most compelling and persuasive rhetoric in all of English literature. His “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven” remains a potent declaration of will, pride, and tragic grandeur. Milton forces readers to confront the uncomfortable tension between Satan’s eloquence and his evil, using language as a mirror to moral ambiguity. In doing so, Milton challenges the reader’s assumptions, making the act of interpretation part of the epic journey itself.

Equally innovative is the way Milton treats time and space through his verse. He transcends earthly geography, guiding the reader through the vastness of Heaven, Hell, Chaos, and Eden. Each location is rendered not just visually, but aurally and emotionally. His description of Chaos, for instance, isn’t merely visual chaos — it is linguistic chaos, a deliberate disruption of rhythm and form to evoke the unformed void. This ability to match content and form elevates *Paradise Lost* to something more than literature — it becomes an experience of the sublime.

Another revolutionary aspect is Milton’s invocation of the muse. Traditionally, epic poets called on the classical Muses for inspiration. Milton, however, invokes the “Heavenly Muse,” directly aligning his poetic authority with the divine. This move repositions poetry not as entertainment or statecraft, but as a sacred act of theological inquiry. He is not merely telling a story; he is illuminating divine truths through poetic form, attempting to “justify the ways of God to men.” This ambition is not just literary — it’s cosmic.

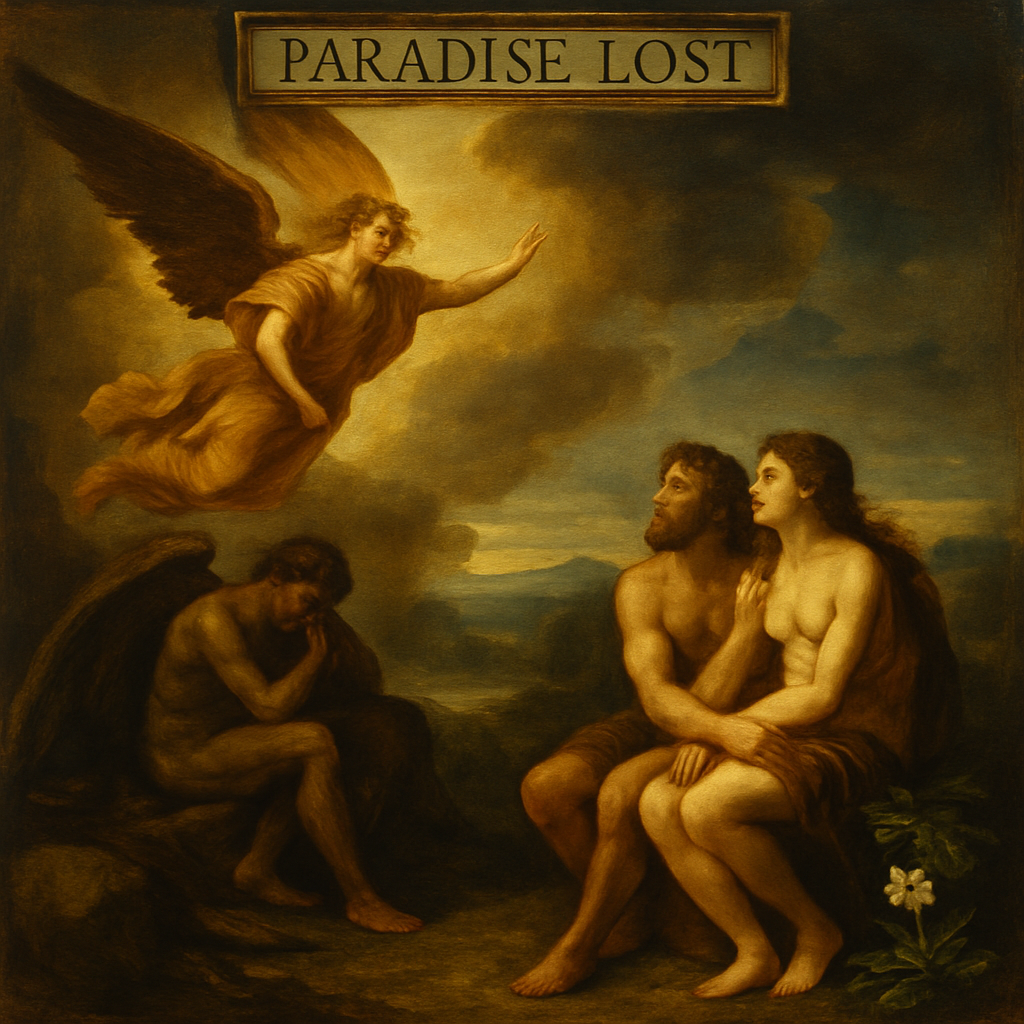

The treatment of Adam and Eve is also central to Milton’s reimagining of the epic. Rather than glorifying military conquest or political power, *Paradise Lost* finds its most emotional depth in a domestic tragedy — the breakdown of trust and love between two people. Milton elevates this personal, relational drama to the scale of epic by linking it with universal themes of freedom, obedience, and redemption. The fall of Adam and Eve is both the end of innocence and the beginning of human self-awareness — a tragedy with redemptive potential, wrapped in linguistic beauty.

Despite its heavy theological themes, *Paradise Lost* never becomes didactic. This is because Milton never simplifies complexity. His poem is filled with unresolved tensions, metaphysical questions, and emotional contradictions. He trusts the reader’s intellect and moral sensibility, and his language reflects that trust. The poem resists easy answers, demanding contemplation and repeated reading. It is language not just as ornament, but as intellectual engagement.

Even today, over 350 years after its publication, Milton’s influence on the English language and literary imagination is profound. Writers from Blake to Wordsworth to Philip Pullman have drawn inspiration from his words. His sentence structures, rhetorical flourishes, and imagery have become part of the DNA of English literature. In a time when attention spans are shrinking and literature is often reduced to utility, Milton stands as a reminder of language’s power to elevate, to provoke, and to endure.

Reading *Paradise Lost* is not easy, nor was it meant to be. But in its difficulty lies its brilliance. It asks us to slow down, to listen, to wrestle with ideas that defy simplicity. And in return, it offers not just poetic pleasure, but philosophical and emotional resonance that grows deeper with time. Milton did not just write an epic — he expanded the very boundaries of what poetry could do.